Spread over two and half months, the 17th Biennale of Sydney concluded early this month reporting an enormous visitation of over half a million people to its seven venues. Cockatoo Island was easily the most popular with audiences not only because visitors were treated to free ferry rides, but also for being an exciting venue that physically transported people away from the rhythms and realities of everyday life into a new, isolated AND massive world of contemporary art waiting to be explored.

Brook Andrew’s Jumping Castle War Memorial. (Australia)

Araya Rasdjarmrearsook’s Manet’s Dejeuner sur I’herbe and the Thai villagers group II – A documentation of a group of Thai villagers, who live near rice farms, discussing and interpreting Manet’s artwork. (Thailand)

Mikala Dwyer’s site-specific installation draws attention to the embodiment of history and memory in archaelogy, and attemptsto resurrect Cockatoo Island’s memories and rouse its ghostly inhabitants. (Sydney)

Yang Fu Dong’s East of Que Village – A six screen video installation juxtaposing stray dogs, who in one instance are seen eating each other for survival, with a small community of villagers who metaphorically struggle in the same way. (Shanghai)

|

|

|

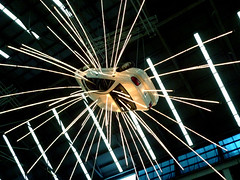

Over 167 artists from 37 different countries came to exhibit based on the curatorial theme “THE BEAUTY OF DISTANCE: Songs of Survival in a Precarious Age”. The first room I entered at Cockatoo Island showcased China artist Cai Guo-Qiang’s Inopportune: Stage One, an installation suspending 9 cars sequentially from ascent to descent with flashing light tubes bursting out from them. The scale and aesthetics of the animated installation was instantly overwhelming. Cai’s work was a display of beauty and violence – a disintegration of their polarities to, instead, signify their existence in one another. Although some of Cai’s critics have taken into account his history as a set designer and hence accused his extravagance of being “hollow”, I admit that I was completely over-excited to see my first Cai Guo-Qiang in Australia, and it was one of the highlights for me.

The 17th Biennale of Sydney was the organization’s largest and most successful exhibition in its 37 years of operation. Biennales are a fantastic platform to see new works by Australian and international artists, and I enjoyed it immensely. What became apparent to me throughout the 3 days of gallery hopping during the biennale was the multiplicity of artistic dialogues between Australia and Asia. However, there still remains a concern in Australia that it faces great risks of being easily left behind at a time where Asia’s art market is booming. Major Australian arts figures are now warning Australia that it is too culturally complacent and need to be much more proactive in having meaningful engagement with Asia. Artistic director and writer Robyn Archer voiced in a 2010 annual forum that “simply touring our product there or importing theirs here squanders the superb opportunities we have to conduct an authentic and highly creative dialogue with Asia through culture and the arts, not a dialogue about the arts but a dialogue about the Asian Century”.

Artitute Contributors

Our art news contributors come from all walks of life. We are on the lookout for regular art patrons who write about the arts. Contact us if you would like to be a contributor on Artitute.com.